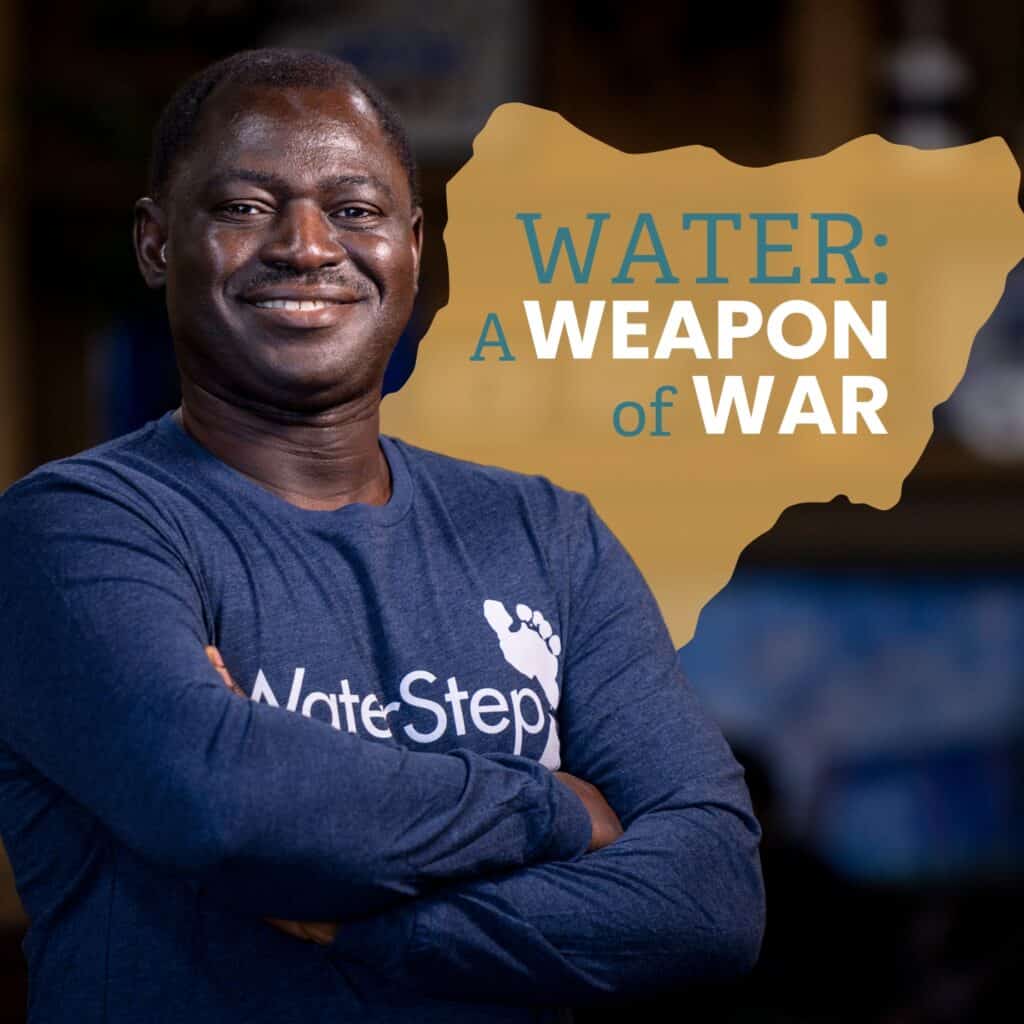

A Nigerian Man Turns Tragedy Into Hope Through Safe Water

“What they used as a weapon, I want to use as a blessing.”

– Nehemiah Maji

Nehemiah Maji still remembers the murky, rancid water of the Ungwan Pama stream in Kaduna state, Nigeria.

He gathered it in clay pots and let the sludge and silt settle before he could drink it. This was the same stream where people washed their clothes and bathed, where animals defecated.

“It smelled like the gutter,” Maji said. “But we had no choice but to drink it.”

Maji, as everyone calls him, grew up in a modern city called Malali where roads were tarred, everyone bought meat and vegetables at the grocery store, and the city piped water to homes from a centralized treatment plant. It was a peaceful time, when Muslims and Christians lived together. They celebrated each other’s holidays, went to the same schools, and ate in each other’s homes.

But in the late 1980s, a radical Muslim cleric changed everything.

“He told Muslims that Kaduna belonged to them, and that Christians were infidels,” Maji said. “These people had been our friends, people we loved. I couldn’t understand why they hated us. They started saying: ‘If you have a chicken that lives with you at home, no matter how long it stays with you, you can slaughter it any day.’ What they were saying was that no matter how long our friendship had been, they wanted to slaughter us.”

In 1992, a riot broke out between the two religious groups. Churches burned. Blood gushed in the street. Bodies covered the roads.

“So many people I knew died,” Maji said. “My uncle. My cousin. Three of my friends. And two pastors I knew.”

Maji was 19 then, finishing his last year of high school.

“I had to walk over corpses on the way to write my last paper,” he said. “I was shivering.”

Because of the fighting, Maji and his family were forced from their homes to an internally displaced persons camp in the south of Kaduna. There was no electricity, no roads, no water.

Cholera and typhoid infected the water. So many people got sick and died.

Over the next five years, batch by batch, more Christians were forced to move to the south.

“If you were wealthy, you could dig a well,” Maji said. “My father did, but it was too close to the latrine, so it got contaminated. Either way, well or not, you risked drinking dirty water – and death.”

The government did not help.

“It was then that I realized they were using water as a weapon of war,” he said. “If they couldn’t kill us with guns, they would kill us with dirty water. We would drink it and die.”

Finally, representatives in the federal government paid to drill a bore hole, but there were so many people who used it, it broke within a few months.

Maji’s family stayed there for nearly two decades. They slowly tried to build a life. Though some became prosperous, most lived in poverty. And the water situation never got better.

In 2021, Maji left Nigeria for good. He’d started an organization called Spurgeon Hope Ministry to help retired pastors, widows, and persecuted Christians. The extremists targeted his family.

“At that time, most of the pastors who were kidnapped never came back,” he said. “So, we had to go into hiding for 6 months.”

Then Maji’s wife received admission to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., and they came to America. Life was good, but he couldn’t forget the people of Kaduna. He had to run the ministry from 5,943 miles away. He implemented programs for retired pastors and oversaw medical outreach for widows. But he wanted to do more.

In May 2024, with WaterStep’s help, Maji established a safe water project in Kaduna, at the border between the north and the south. He insisted that Muslims and Christians build it together on the border between northern and southern Kaduna — a place where the lines between religious groups had long been drawn in blood.

“We put a tank as high as possible so everyone can see it,” he said. “The 6,500 Christians in the south use it for safe drinking. And the 30,000 Muslims who have access to water from the government on the north side can use it, too. Because their electricity is not stable. And if there’s no electricity, there’s no water.”

Anyone can come and collect water, Maji said. Muslims. Christians. Hindus. People of faith and those with no faith at all. Safe water is not just a life-sustaining resource, he said. It’s a symbol of peace, healing, and the power to bridge even the deepest divides.

“I hold no bitterness toward anyone there,” Maji said. “People I love still live there. Christians and Muslims. I believe in forgiveness, and I believe in peace. What they took away from me, I want to give. What they used as a weapon, I want to use as a blessing.

“As a pastor, I know the Bible says if your enemy is thirsty, give him water. When people want to eliminate you, they want to see you dead; they see you as their enemy. But I still see them as my friends.”

Please support our global safe water work by donating today:

Follow our pages on social media for more updates and stories like this: