South Sudanese Man Endured War to Bring Hope Home

“I am bringing a new kind of privilege back to my family, my village, and my father’s name.”

— Simon Ottaviano

When Simon Ottaviano started primary school, he sat under the leathery leaves of an African fig tree, learning to write letters in the dirt with his finger. He sang songs about the history of Acholiland, in Magwi County, the place of his tribe in South Sudan.

Everyone knew Simon’s name. His father, Ottaviano Oyat, was paramount chief — chief of all chiefs of the Acholi. In class, his father’s name was often the answer to history questions.

“Despite my privilege and high social status, water was a problem,” Simon said. “We just didn’t realize it.”

Prisoners carried water from the River Ayii and poured it into large clay pots in his family compound. There was no way to know how long the water had been there and no way to test or treat it. Often, people were sick.

“The whole village suffered from bilharzia,” he said. “It’s a parasitic worm that can eat your intestines. Sometimes, I would try a local medicine of boiled herbs, but that would only help for a few days. Three or four times a week, I would see blood when I went to the bathroom. There were no hospitals or clinics in my village, so health was a serious problem. People suffered. Your stomach is paining, and there is no way out. You live with it every day.

“Still, I felt I lived a privileged life.”

What Simon couldn’t fathom on the days he drew letters in the dirt was that his experience of cycling from privilege to destitution and back would not only change his life but the people in his homeland. It would take 30 years of fear, abandonment, loneliness, hope and personal will.

But first he’d have to escape war.

WAR DESTROYS EVERYTHING

When Simon was 13, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, a rebel group, formed. War erupted, and his country’s government collapsed. By the time he turned 16, killing arrived in his village.

“That day my privilege disappeared,” he said.

The moment, the hour, is seared on is heart. It was 3 p.m., and Simon was in an open-air church with his siblings. Gunshots silenced the hundreds of voices in hymn.

“I could hear shooting left and right,” he said. “People were running. Screaming. I saw people I knew laying on the ground, bleeding from bullet wounds.”

Simon’s mom and dad, meko and weko, ran with their children to hide. They could do nothing as they watched rebels set fire to everything they had. They stayed in the bush for a week.

“I was with a large group of people sitting under a tree by the river — about 200 of us,” Simon remembered. “We couldn’t go by the road because we knew we’d be attacked. And we needed the river for water because there was nothing left of the village.”

One afternoon, he saw people running before he heard the guns. In 15 seconds, he could no longer see his parents and wouldn’t again for another 10 years. The rebels needed a strategic position for running guns from Uganda, and his people had to move.

For the next two weeks, Simon walked with people he didn’t know. Women cried, children cried as they followed the river and the mountains — always close to drinking water — until they reached a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya.

They finally had what they needed: Water to drink. Clothes to wear. Food to eat. And a blanket.

“Coming from a privileged family I had never collected water,” he said. “It was not something the chief’s son was expected to do. I had never washed my own clothes. But there I was at 16 years old. Alone and fetching water on my own.”

Simon stayed in the camp for a year and then moved to another nearby camp called Ifo for an additional six months. There, the International Organization for Immigration filed paperwork for boys like him to resettle in another country.

“I was chosen to come to America,” Simon said. “I was 19 years old.”

AMERICAN PRIVILEGE: A FAUCET AND A LIGHT SWITCH

Simon arrived in Maine in the middle of winter. The temperature was so cold he thought his ears might fall off. He was in awe of how people lived.

“I experienced a whole different level of privilege for the first time,” Simon said. “I didn’t understand electricity, so I flipped the light switch on and off. When I turned the faucet on, it was running. I had no idea where the water was coming from or where it was going. I kept flushing the toilet.”

He no longer had stomach pain and, gradually, forgot he ever had it.

Slowly, he made a life for himself in America.

BRINGING PRIVILEGE HOME

Simon has been in the United States for 30 years now. He married a fellow South Sudanese woman he met in Louisville, and they had five children. Over the years, they’ve sent money back home for small projects. But Simon had bigger dreams. So, in 2021, with his wife’s support, he sold their house and cashed out his 401k to build a school in Magwi.

In 2022, Ayaa Senior Secondary School, named for his mother, opened to much celebration. But every month the head teacher spent 600,000 South Sudanese pounds (about $100 U.S. dollars) on tanker trucks that collected dirty water from the River Ayii — the same one Simon drank from and bathed in as a boy — and dumped it into barrels on campus. Otto Clement, the school’s director of studies, said the school was forced to spend six times a teacher’s monthly salary every 30 days to keep water at the school.

It wasn’t safe to drink, and 300 students often suffered from typhoid and bilharzia. The cost of typhoid treatment alone was often more expensive than what families paid in tuition.

“You only pray that you don’t get sick,” Okello Isaac, the school’s head teacher said.

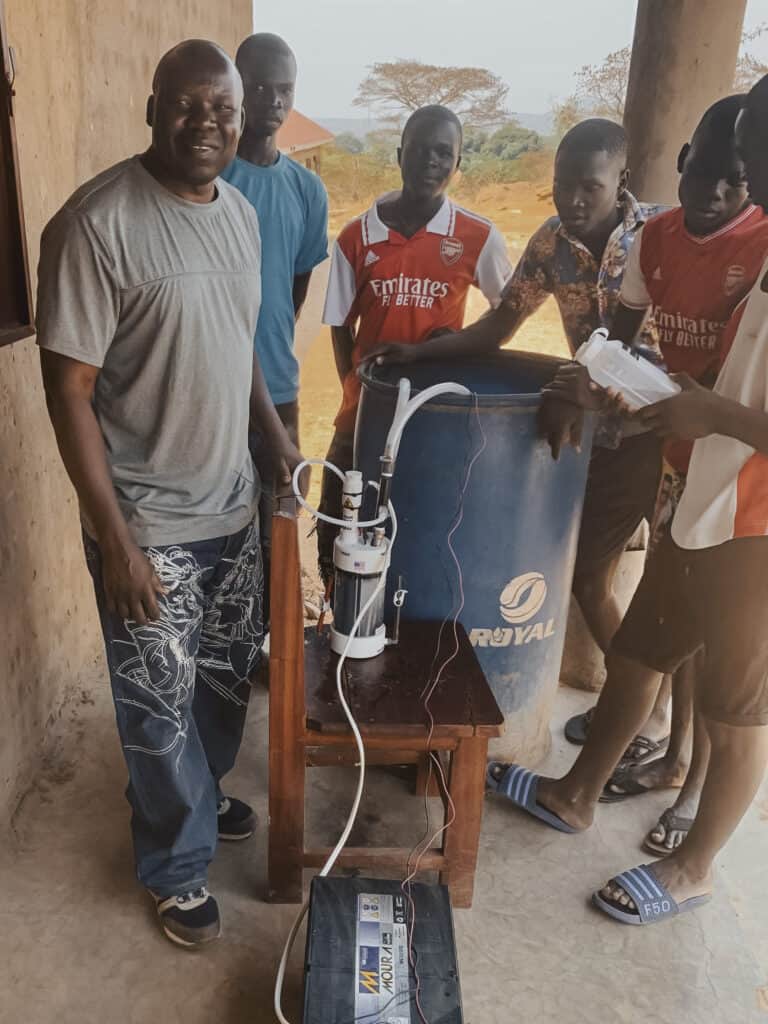

In 2023, Simon brought WaterStep’s safe water system to the school, so officials no longer have to pay for tanker trucks of unsafe river water. Students have safe water to drink and bleach to keep the school sanitized and safe from germs. And the savings means school officials can spend the money on books and to hire more teachers.

Most importantly, there’s been a dramatic reduction in cases of student illness.

“When you have healthy students, they are going to enjoy their studies,” Okello said. “You just have a conducive, peaceful environment.”

A DREAM COME TRUE

Simon’s school remains a work in progress, but he’s proud of what he’s accomplished thus far.

“Today, I can proudly say I am still the son of Chief Ottaviano Oyat,” Simon said. “By my birth, I was born into privilege. But because of my experience — and WaterStep — I am bringing a new kind of privilege back to my family, my village, and my father’s name.”

Simon can still remember in his parents’ house the silver cup they used to scoop water from the clay pot and the parasitic worms wriggling on the surface. He can still hear the voice of his mother, who died long ago, telling him the water needs to be changed.

Now, Simon is the change.

“I am bringing safe water back to my village and to the school I built so children don’t have to suffer from those parasitic worms that eat your intestines,” he said. “Their stomachs won’t hurt all the time. They won’t see blood when they go to the bathroom.

“I don’t know if my own name will be the answer to history questions about our Acholi tribe in the next 10 or 15 years like my father’s was. But I know I’m working right now to rewrite history for the next generation for the Acholi.”

Please support our global safe water work by donating today:

Follow our pages on social media for more updates and stories like this: